On Wednesdays for the past few weeks, a band of lifesavers has walked the streets of Healdsburg, popping into shops and talking to owners and store managers about Narcan. Two retired physicians, David Anderson and Walter Maack, join Jeff McGee, the police department’s Social Services team member, and sometimes other members of the Harm Reduction Coalition.

Among their other works, that ad hoc collection of locals in the medical field has taken up placing needle-disposal kiosks in town; now they’ve taken on the mission of getting Narcan into the hands of those who need it—not just users, but their relatives, at work and in public places as well.

Opioid overdose cases began to climb in 2013, and by the end of the decade the rate was still skyrocketing. So the Harm Reduction Coalition began to do public outreach about health dangers. Narcan is a near-miraculous cure for coma induced by heroin or fentanyl, the most well-known synthetic opioid. But Narcan works on heroin as well, or any opioid—it’s the wide presence of fentanyl that makes administering the cure so vital.

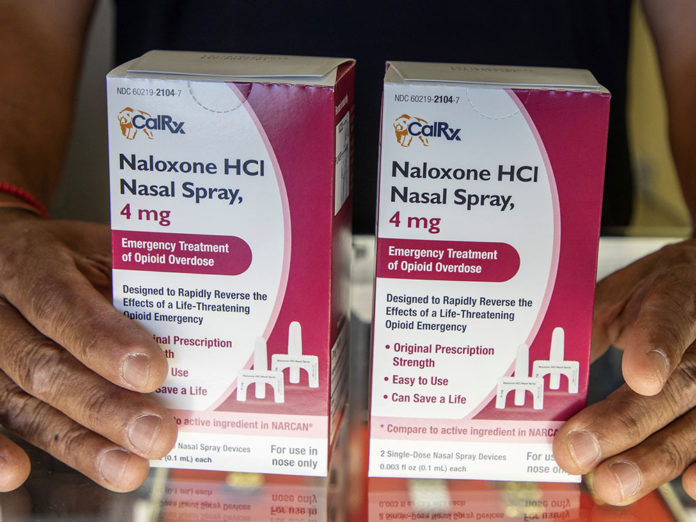

Unlike an AED, or automated external defibrillator, that can be used to treat a person whose heart has suddenly stopped working, administering Narcan is simple: It’s a nasal spray. A brand name of naloxone, Narcan is an opioid antagonist that blocks the effects of opioids on the body’s receptors at a cellular level. It works almost immediately.

In March, Alliance Medical Center received 2,400 units of Narcan and 2,500 fentanyl test strips from the state Naloxone Distribution Project, according to substance abuse counselor Bobby Choate. The Harm Reduction Coalition, of which Choate is a member, took it upon itself to distribute the materials free to the community.

Will Gayowski, head of the Sonoma County Health Services section dealing with substance abuse, warned on June 16 of a recent spike of fentanyl-related fatalities: 12 in the previous two weeks.

While these deaths were among men between the ages of 19 and 59, the population most at risk for opioid overdose are older adults, and persons who often use prescription opioids to cope with acute surgical pain or chronic conditions.

Which means the risk of opioid overdoses could be closer to home than most of us think. Dr. Walter Maack was an emergency room doctor at Healdsburg Hospital for years, until his retirement in 2016. A year later his oldest son, who had struggled with substance abuse earlier in life, died of a heroin overdose when he briefly went back to the drug.

The timing of the opioid crisis from overprescription of Oxycontin, the arrival of the dangerously strong synthetic opioid fentanyl and Maack’s own family story helped crystallize the mission of the Harm Reduction Coalition.

“Pure and simple, I want to honor his memory and do something rather than nothing,” Maack said. “It helps with the grief, which of course never goes away, but I just feel like I’m doing something.”

The Narcan distribution group is but the latest effort of the Harm Reduction Coalition, whose works stretch back several years, initially as a blood-pressure watch group. The Coalition’s interpretation of its mission is broad.

It helps spread availability to Narcan, two doses per red-and-white box, and fentanyl test strips to anyone who has come into possession of a narcotic they’re not sure about.

Another member of the coalition is Jeff McGee, a certified social worker employed by the police department. He’s quick to say he’s not a sworn officer, doesn’t carry a gun and can’t make arrests. Instead his job, formally Critical Intervention Specialist, is to be on the street where necessary, when needed, interacting with people who might be experiencing a crisis moment.

He has witnessed the problem with overdosing firsthand, of course, but is thankful it hasn’t been too prevalent in Healdsburg as yet. “I think it’s definitely here in Healdsburg. And it’s something that we’re seeing pop up in Santa Rosa. We’re seeing it pop up in Cloverdale,” McGee said.

“Part of the Narcan distribution program is spreading awareness, and giving people something that they can do to help counteract the issue,” he added. “I think it’s really important to help empower the community and help kind of bring awareness that this is an issue that can affect everyone and anyone.”

For the past several Wednesdays, and perhaps a few more to come, the Narcan Squad has gone to the downtown commercial areas of Healdsburg, including Vineyard Plaza as well as the central area. The squad goes to every door in the area and makes the pitch: “Here’s free Narcan you can have on hand in case there’s an overdose in the store, or outside, so you can help.” The boxes are red and white, with two nasal spray doses each and clear instructions on how to use them.

Most people the squad approaches are more than willing to take them. “We’re in and out of the store within two minutes,” Anderson said. “We encourage them to make sure all their employees know where it is, and what it’s for.”

Anderson spoke to one store owner who said that his son has a peanut allergy, so he carries an EpiPen with him. “So he knows how these things happen, how you have to act quickly,” the doctor said.

Narcan is now in police cars including the chief’s car, and in most first responder vehicles, thanks in part to the Harm Reduction Coalition’s efforts.

“It’s as close to a wonder drug as you can get,” Maack said, “where you reverse a person who’s turned blue and not breathing—in minutes, they pink up and start breathing again. That’s so incredible to see.”

Does that mean there have been no instances of dangerous overdoses, or overdose deaths in Healdsburg in the last 3 years?

If not, how many cases? Over what time period? Please be specific regarding important topics like this.

According to Bell’s Ambulance, they administered 44 doses of Narcan in 2023. Most within Healdsburg. Also the Healdsburg Police Department administered some. Despite this, at least 4 young men died in the last several years of opioid overdose locally.